New use for plastic waste being developed

Case Western Reserve researchers developing process to recycle ‘thermoset’ plastics; examples include wind-turbine blades, auto parts, boats, other structural materials

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University have developed a new technology that could change non-recyclable plastics into recyclable ones and reprocess them into new products with comparable or even higher value.

Those non-recyclable plastics, known as thermoset polymers, are often used in mechanical strong and lightweight applications in the automotive, aerospace and wind industries, as well as for countless commercial uses—from plastic chairs to toys and more.

But thermosets—unlike thermoplastics, their softer and easily recyclable polymer cousins—can’t be remolded once cured. In other words, they are single use and not recyclable in any meaningful way. So thermoset products either end up in landfills or are burned as fuel, both of which hurt the environment.

The new work at Case Western Reserve may change that.

Ica Manas-Zloczower

Leading the research and development is Ica Manas-Zloczower, Distinguished University Professor and the Thomas W. and Nancy P. Seitz Professor of Advanced Materials and Energy in Macromolecular Science and Engineering, and Liang Yue, a post-doctoral researcher in Manas-Zloczower’s lab.

Manas-Zloczower and Yue have found a new way to take the previously rigid thermoset plastics and break them down into a resin that can be used to remake the product, or make an entirely new product—just as with the softer thermoplastics.

“Many of the plastic commercial products we use are thermoplastic and are already easy to process, but the thermoset materials in construction, aerospace, aircraft and automobiles are the problem,” Yue said. “These are strong materials and resistant to impact, but until now they were single use. We’re trying to change that.”

‘Vitrimerization’ process makes recycling possible

A strong chemical cross-linked molecular network is what makes thermoset plastics resistant to heat, corrosion and other environmental factors. That same strength, however, also makes them far more difficult to break down and recycle.

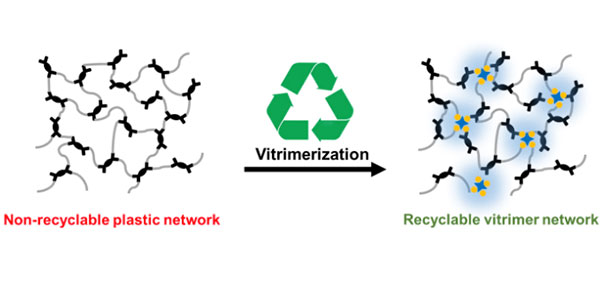

Manas-Zloczower and Yue are solving this problem by converting permanent, cross-linked structures into dynamic cross-linked ones.

The dynamic cross-linked network allows reshaping and reprocessing by conventional methods, such as hot-press molding or injection molding, to fabricate a new product with comparable or better value.

Yue began working on the concept in Manas-Zloczower’s Case School of Engineering lab in 2018, using a solvent-assisted approach to diffuse the appropriate catalyst into epoxy and polyurethane networks.

They call the new process “vitrimerization” because it converts the thermoset plastics into a new class of materials known as vitrimer polymers, which can be reformed and reprocessed.

So far, Yue has performed the experiment with small amounts of material in the lab. But he and Manas-Zloczower are in discussions with industrial partners about using a process known as “mechanochemical ball-milling” to produce tons of reusable powder resin, with no solvent involved.

That makes the process much easier to “scale up in a meaningful way,” Yue said. “We can recycle tons of epoxy waste in a matter of hours now. Initially, with a catalyst and solvent, even at smaller scale, it took much longer.”

Their research was published earlier this year in the journal ACS Macro Letters and followed a 2019 paper that introduced the first iteration of vitrimerization.

Manas-Zloczower said the work over the last two years was funded in part by the National Science Foundation, but that she and Yue are working closely with the Great Lakes Energy Institute and Case Western Reserve’s Office of Technology Transfer to identify potential industry partners, research funders, or investors to take the next steps toward fully testing the process at industrial scale.

“As a nation and a world, we’re looking to find ways to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and to ultimately stop drilling for oil and gas,” said Grant Goodrich, executive director of the Great Lakes Energy Institute at Case Western Reserve. “We can’t achieve or sustain that without recycling the plastics we have, since petroleum is the raw material in nearly all plastic products.”

For more information, contact Mike Scott @mike.scott@case.edu

(From The Daily, 6/23/2020)