When Herbert Dow arrived for his first year at our predecessor institution the Case School of Applied Science in 1884, just four years after the college opened, he didn't envision that he would later found one of the world's largest chemical companies.

But Dow came to an environment where curiosity, creativity and initiative dominate—one where students and faculty inspire each other in discovery and innovation. Across campus, professors Albert Michelson and Edward Morley were carrying out one of the most important experiments in the history of physics, proving that light does not propagate through an ‘ether.’ Michelson was the first American to win a Nobel prize (in 1908) for this work.

Dow’s scientific and entrepreneurial interests thrived in this intellectually charged atmosphere. With technical, financial and moral support from his classmates, he went on to start a small company after completing his undergraduate degree. The Dow Chemical Company is now among the largest in the world.

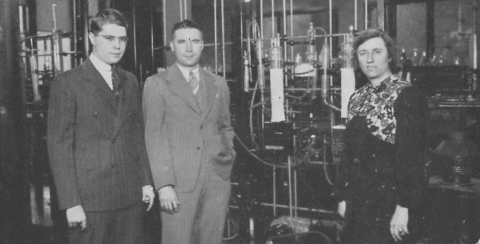

Herbert Dow’s success was just the beginning. In the 1920s, two sons of Albert W. Smith, Dow’s classmate and later a professor at Case Western Reserve, studied chemical engineering at the university. After graduating, Kent and Kelvin Smith teamed up with classmate Alex Nason to found the Lubrizol Corporation—now a Fortune 500 company.

In the 1960s and 70s, chemical engineering professor John Angus set out to do what seemed impossible: making diamonds at low pressures, where graphite rather than diamond is thermodynamically stable. Angus showed how to use kinetics rather than thermodynamics to “trick” the material into becoming diamond, and was elected to the prestigious National Academy of Engineering for this discovery.

The tradition of curiosity, creativity and initiative continues in our department. Our graduates become leaders in the chemical industry, and our research thrives at the cutting edge—ranging from fundamental molecular scale science to plant-scale industrial projects. We study topics as varied as energy, advanced materials and biological engineering. In many cases our research is in collaboration with industrial partners, from Intel to Nestle. Many of our research projects include interdisciplinary collaborations, with partners as diverse as geologists and medical doctors.

In 2014, the department changed its name to the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering to better reflect the depth and breadth of our research programs and academic offerings.

Check out our current research initiatives for a hint of breakthroughs to come.