Surface Engineering

Many technical applications of materials—from screws to ball bearings to hip implants—require parts that possess complex shapes and perform under mechanical impact and/or in aggressive chemical environments. However, the materials properties needed for optimal resistance to environmental impact usually differ from the properties needed for complex forming. This apparent dilemma can be resolved by first forming and machining the part and then providing it with suitable properties for service only where they are needed to resist environmental impact: at the surface.

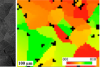

The innovative approach we are pursuing to such surface engineering of alloy parts is to expose them to gases that provide carbon or nitrogen atoms to diffuse into the alloy. Under carefully controlled conditions, this can generate a subsurface zone with very high concentrations of uniformly dissolved carbon or nitrogen, providing greatly improved properties and performance. For austenitic stainless steel, for example, carbon or nitrogen concentrations can be accomplished that triple the hardness, improve both the wear resistance and the high-cycle fatigue resistance by about 100 times, and provide a saltwater corrosion resistance that outperforms that of the most expensive corrosion-resistant alloys. Different from competing approaches, such as coatings, the process is highly shape conformal and generates smoothly graded concentration—depth profiles, rather than abrupt coating—substrate interfaces where, for example, insufficient adhesion or stress concentration may become a lifetime-limiting problem.

Current research targets comprehensive physical understanding of the underlying microscopic mechanisms and the development of new processing schemes that will enable applying this method of surface engineering in a time- and cost-efficient way that is suitable for mass production of parts made from a broad variety of alloys for a correspondingly broad spectrum of technical applications.

Institutes, centers and labs related to Surface Engineering

Faculty who conduct research in Surface Engineering

Frank Ernst

David Matthiesen